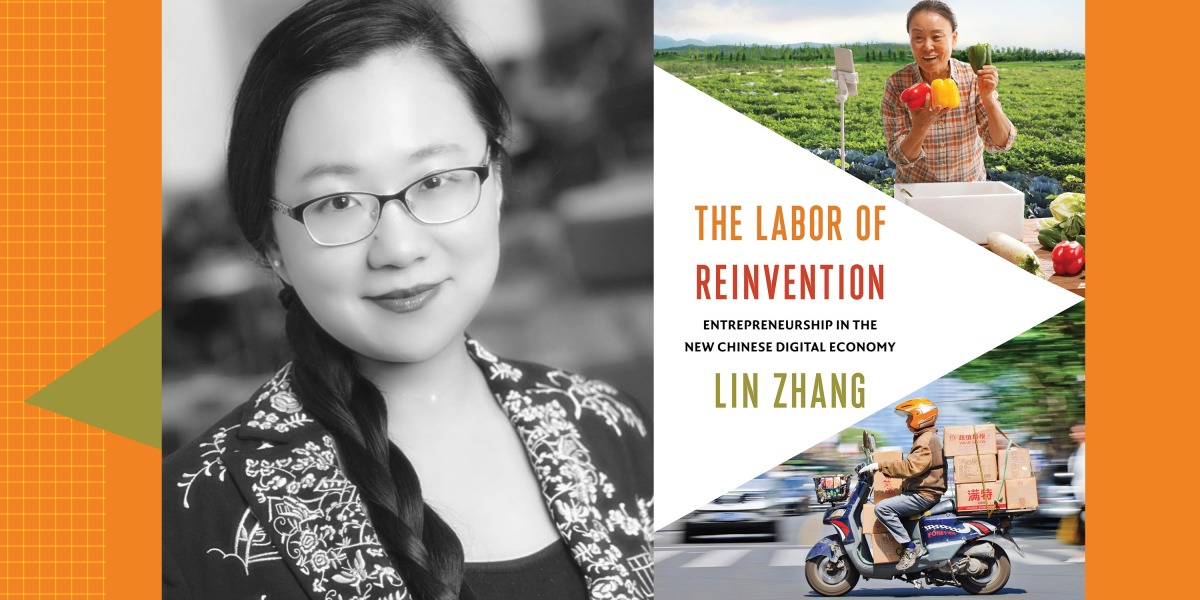

I recently talked about this with Lin Zhang, assistant professor of communications and media studies at the University of New Hampshire and author of a new book: The Labor of Reinvention: Entrepreneurship in the New Chinese Digital Economy. Based on a decade of research and interviews, the book explores the rise and social impact of Chinese people who have succeeded (at least temporarily) as entrepreneurs, particularly those working within the digital economy.

In the not-so-distant past, China was obsessed with entrepreneurship. At the Davos conference in the summer of 2014, Li Keqiang, China’s premier, called for a “mass entrepreneurship and innovation” campaign. “A new wave of grassroots entrepreneurship… will keep the engine of China’s economic development up to date,” he declared.

Tech platforms, which have provided entry points to the digital economy for many new entrepreneurs, also joined the government’s campaign. Jack Ma, founder of the e-commerce empire Alibaba and a former English teacher, said in 2018: “If people like me can succeed, then 80% of [the] young people in China and around the world can do so, too.” Alibaba often touts itself as a champion of small online businesses and even invited one rural seller to its bell-ringing ceremony in New York in 2014. (Eventually, the relationship between the state and moguls like Ma would become much more fraught, though the book focuses on people who use platforms like Alibaba, rather than on the country’s tech titans who founded them.)

At the core of this campaign is an alluring idea the country’s most powerful voices are reinforcing: Everyone has the chance to be an entrepreneur thanks to the vast new opportunities in China’s digital economy. One key element to this promise, as the title of Zhang’s book implies, is that to succeed, people have to constantly reinvent themselves: leave their stable jobs, learn new skills and new platforms, and take advantage of their niche networks and experiences—which might have been looked down upon in the past—and use them as assets in running a new business.

Many Chinese people of various ages and genders, and of differing educational and economic backgrounds, have heeded the call. In the book, Zhang zooms in on three types of entrepreneurs:

- Silicon Valley-style startup founders in Beijing, who have capitalized the most on the government’s obsession with entrepreneurship.

- Rural e-commerce sellers on the popular shopping platform Taobao, who employ their own families and neighbors to turn local crafts into profitable businesses.

- Daigou, the often-female resellers who buy luxury fashion goods from abroad and sell them to China’s middle-class consumers through gray markets on social media.

What interests me most about their stories is how, despite their differences, they all reveal the ways entrepreneurship in China falls short of its egalitarian promises.

Let’s take the rural Taobao sellers as an example. Inspired by a cousin who quit his factory job and became a Taobao seller, Zhang went to live in a rural village in eastern China to observe people who came back to the countryside after working in the city and reinvented themselves as entrepreneurs selling the local traditional product—in this case, clothing or furniture woven from straw.

Zhang found that while some of the owners of e-commerce shops became well-off and famous, they only shared a small slice of the profits with the workers they hired to grow the business—often elderly women in their families or from neighboring households. And the state ignored those workers when bragging about entrepreneurship in rural China.