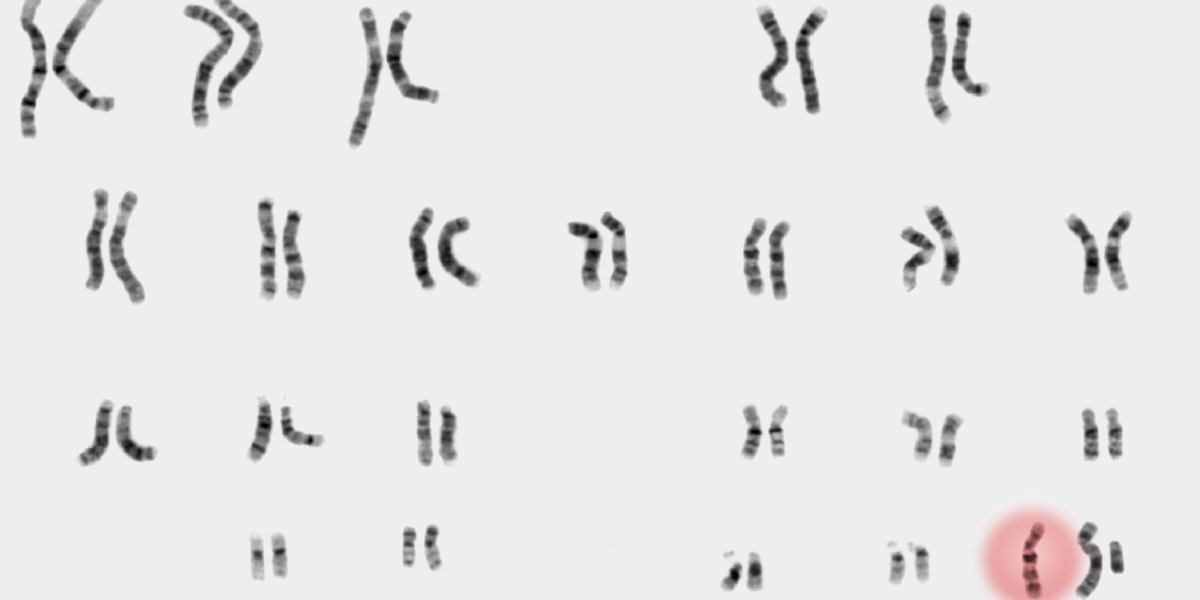

Katie and her husband, Simon, had never heard of XXY, and their obstetrician wasn’t much help either. Also known as Klinefelter syndrome, XXY is a genetic condition that can cause infertility and other health issues; it occurs when a child, typically assigned male at birth, is born with an extra X chromosome in addition to the usual X and Y.

Sex chromosome variations, in which people have a surplus or missing X or Y, are the most common chromosomal conditions, occurring in as many as one in 400 births. Yet the majority of people affected don’t even know they have them. That’s because these conditions can fly under the radar; they’re not life threatening or necessarily even life limiting and don’t often have telltale characteristics that raise red flags. Still, the diagnosis can cause distress.

As more expectant parents opt for noninvasive prenatal testing in hopes of ruling out serious conditions, many of them are surprised to discover instead that their fetus has a far less severe—but far less well-known—condition. Because so many sex chromosome variations have historically gone undiagnosed, many ob-gyns are not familiar with these conditions, leaving families to navigate the unexpected news on their own. Many wind up seeking information from advocacy organizations, genetic counselors, even Instagram as they figure out their next steps.

The information landscape has shifted dramatically since the advent of noninvasive prenatal screening (NIPS) a decade ago. The increasingly popular first-trimester blood tests that debuted in 2011 to detect Down syndrome have, over time, added a broader spectrum of conditions to their panel, including sex chromosome aneuploidies—the medical name for an atypical number of chromosomes.

“The scariest part is here is this diagnosis based on a test that we didn’t really understand.”

In 2020, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists endorsed NIPS at any age, effectively making the blood test a routine part of pregnancy care. Parents typically use these tests to rule out Down syndrome or more severe conditions, only to find out in many cases about something they didn’t even realize their baby was being screened for. “The scariest part is here is this diagnosis based on a test that we didn’t really understand,” says Simon. Adds Katie: “We were assuming the test would detect only very serious things.”

To add to the complexity, NIPS is not as reliable for sex chromosome aneuploidies as it is for Down syndrome, underscoring the importance of confirming a positive screening result during pregnancy via amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (which examines placental tissue), or with a blood sample after the baby is born. Yet data suggests that “some women have elected to terminate pregnancies solely on the basis of [noninvasive prenatal screening] results, potentially aborting unaffected fetuses,” according to a 2016 article in Prenatal Diagnosis.

About 40% of men with XXY are diagnosed over the course of their lifetimes, usually when they experience fertility problems as adults, says Nicole Tartaglia, a global expert on sex chromosome variations. People with XXY may have learning difficulties and challenges with social interaction, along with physical traits such as small testes, a less muscular body, and less facial and body hair. But most people with Klinefelter syndrome grow up to live productive, healthy lives.

Meanwhile, only 10% of people with XXX or XYY are aware of their condition. But these numbers are growing as genetic testing becomes more widespread. “Judging by the number of phone calls we are getting, the proportion of those who are going undiagnosed is getting smaller,” she says.