The “cat-and-mouse game,” as it’s usually referred to locally, has gone viral in China this year, drawing thousands of people across the country to events every week. It’s a fun combination of a childhood game, in-person networking, the latest location-sharing technology, and meme-worthy experience. When the game first emerged in February, videos of hide-and-seek players who went wild—climbing up trees, hiding in the sewers—got millions of views on social media.

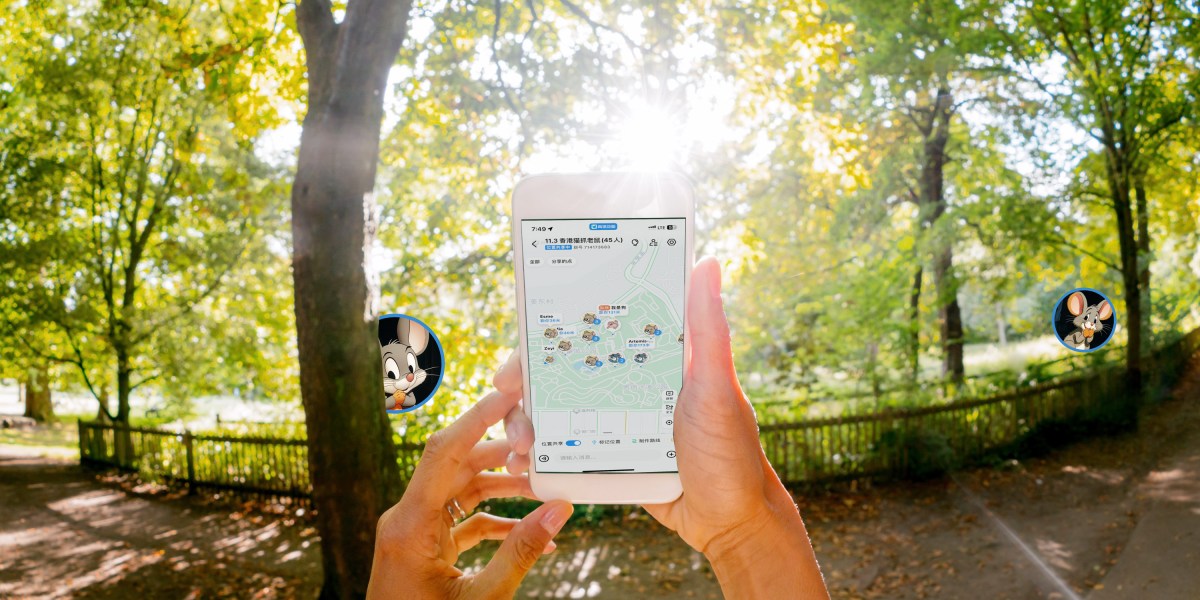

Each contest convenes dozens of people in a predetermined area, often a large city park. All of them then join a group on Amap, a Chinese Google Maps alternative, and share their live location. Among the participants, 90% are designated as “mice” and have five minutes to run and hide. Then the rest, who are “cats,” will go out and hunt down each mouse with the help of the location sharing, as well as a neon wristband that visually separates them from nonparticipants. Once caught, the mice switch teams and join the cats, so the game gets harder and harder for the remaining mice.

During a short trip to Hong Kong last month, I joined two cat-and-mouse games in the city. Both of them had about 40 participants and lasted one hour. The first park was larger and had fewer people, meaning it was prime for running and chasing; the second was crowded and smaller, which made it ideal for trying to blend in with passersby.

Being an indoor person, I’m not always a fan of group physical activities, but the two experiences went far beyond my expectations. The addition of location sharing has turned the kids’ game into a more interactive version of Pokémon Go. Trying to remain hidden in the same spot throughout the game was not possible, since the cats could always see where I was; I needed to get more creative in crafting an escape plan. I quickly learned that deception—hiding my glowing bracelet, pretending to be an innocent jogger, and avoiding checking my phone too often—was also essential to being a good mouse.

Just watching everyone’s locations in the app was an intense experience. Dozens of little avatars were floating around in the park at once, with cats gradually outnumbering mice as the game progressed. Delays and bugs were plenty, but that added to the fun and difficulty of the game. I could feel safe at one moment, seeing there were no cats around, and panic seconds later when a cat suddenly moved hundreds of feet toward me, likely because its location sharing had lagged.

As a first-timer, I did okay. For my first game, I survived as a mouse until the last few minutes, when mostly everyone else had converted to the cat side. For my second outing, I converted mid-game and caught two mice myself.

I’ll readily admit some people were much better than I was. Hong Shizhe, a 19-year-old college student, was crowned the “cat king” of the second game, having caught 11 mice by the end. “I like that you can both exercise and have fun in this activity,” Hong says. He first learned about the game through videos people shared on Chinese social media, and he has been to several games in Hong Kong and mainland China since. He told me the largest one had more than 140 participants. Once, he even took his dog to the park with him and still won the game.

His secret for success? A lot of lies and politics: “You can make a deal with the mice and have them help you find other little mice. You can also pretend to be a mouse and strike up a chat with them.”