Although later studies questioned the detection of phosphine, the initial study reignited interest in Venus. In its wake, NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) selected three new missions to travel to the planet and investigate, among other questions, whether its conditions could have supported life in the past. China and India, too, have plans to send missions to Venus. “Phosphine reminded everybody how poorly characterized [this planet] was,” says Colin Wilson at the University of Oxford, one of the deputy lead scientists on Europe’s Venus mission, EnVision.

But the bulk of those missions would not return results until later in the 2020s or into the 2030s. Astronomers wanted answers now. As luck would have it, so did Peter Beck, the CEO of the New Zealand–based launch company Rocket Lab. Long fascinated by Venus, Beck was contacted by a group of MIT scientists about a bold mission that could use one of the company’s rockets to hunt for life on Venus much sooner—with a launch in 2023. (A backup launch window is available in January 2025.)

Phosphine or no, scientists think that if life does exist on Venus, it might be in the form of microbes inside tiny droplets of sulfuric acid that float high above the planet. While the surface appears largely inhospitable, with temperatures hot enough to melt lead and pressures similar to those at the bottom of Earth’s oceans, conditions about 45 to 60 kilometers above the ground in the clouds of Venus are significantly more temperate.

“I’ve always felt that Venus has got a hard rap,” says Beck. “The discovery of phosphine was the catalyst. We need to go to Venus to look for life.”

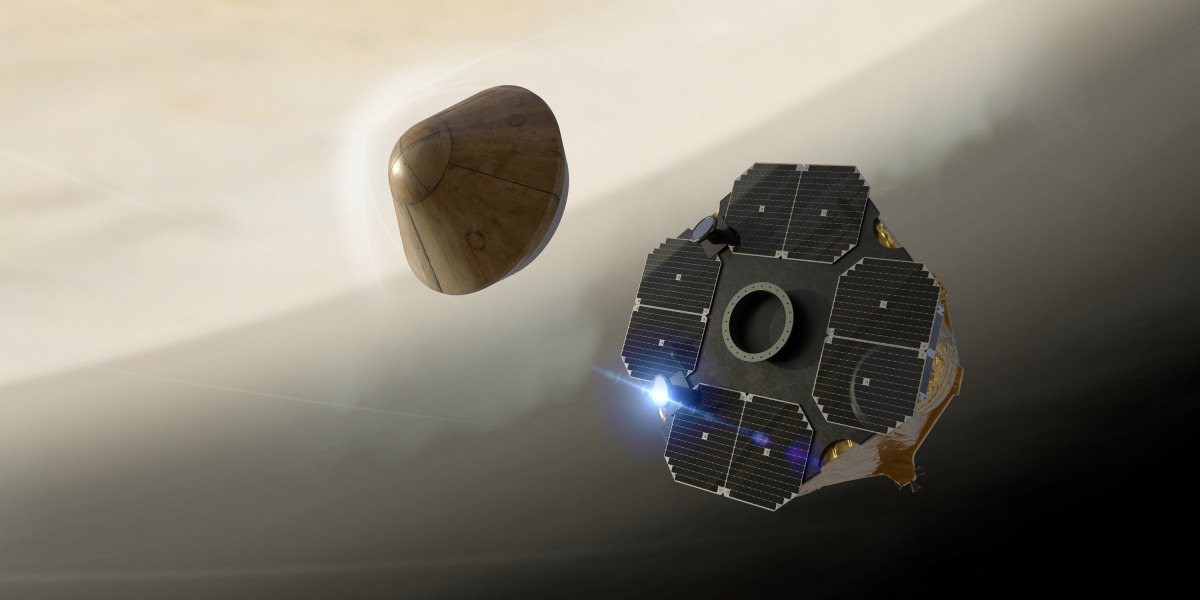

Details of the mission, the first privately funded venture to another planet, have now been published. Rocket Lab has developed a small multipurpose spacecraft called Photon, the size of a dining table, that can be sent to multiple locations in the solar system. A mission to the moon for NASA was launched in June. For this Venus mission, another Photon spacecraft will be used to throw a small probe into the planet’s atmosphere.

That probe is currently being developed by a team of fewer than 30 people, led by Sara Seager at MIT. Launching as soon as May 2023, it should take five months to reach Venus, arriving in October 2023. At less than $10 million, the mission—funded by Rocket Lab, MIT, and undisclosed philanthropists—is high risk but low cost, just 2% of the price for each of NASA’s Venus missions.

“This is the simplest, cheapest, and best thing you could do to try and make a great discovery,” says Seager.

The probe is small, weighing just 45 pounds and measuring 15 inches across, slightly larger than a basketball hoop. Its cone-shaped design sports a heat shield at the front, which will bear the brunt of the intense heat generated as the probe—released by the Photon craft before arrival—hits the Venusian atmosphere at 40,000 kilometers per hour.