Jeremy Thompson, an embryologist based in Adelaide, Australia, says he’s spent his career figuring out “how to make the lives of embryos better” as they grow in laboratories. But until recently, he says, his tinkering with microfluidic systems yielded an unambiguous result: “Bollocks. It didn’t work.” Thompson says IVF remains a manual process in part because no one wants to trust an embryo—a potential person—to a microdevice where it could get trapped or harmed by something as tiny as an air bubble.

FERTILIS

A few years ago, though, Thompson saw images of a minuscule Eiffel Tower, just one millimeter tall. It had been made using a new type of additive 3D printing, in which light beams are aimed to harden liquid polymers. He decided this was the needed breakthrough, because it would let him build “a box or a cage around an embryo.”

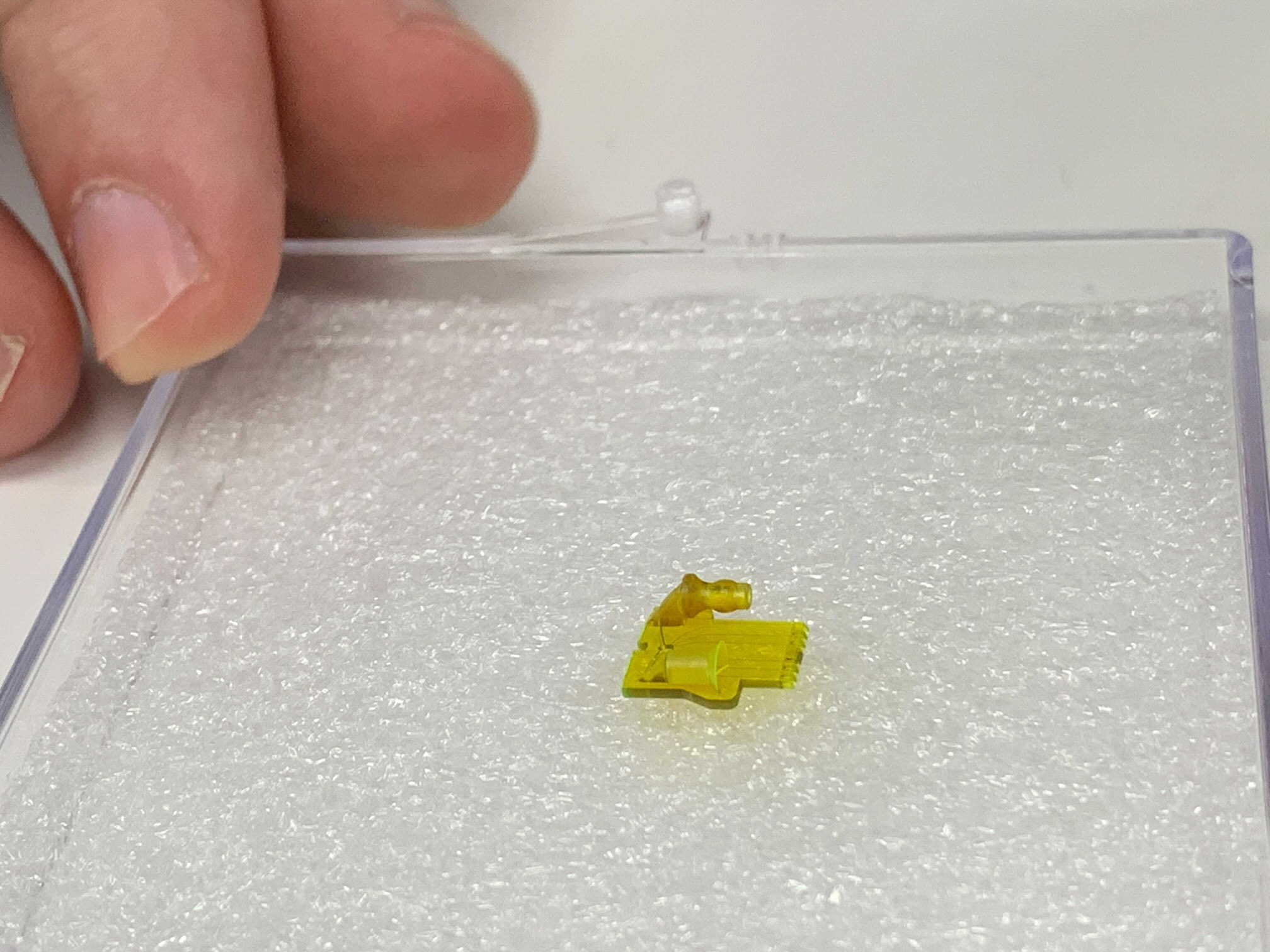

Since then, a startup he founded, Fertilis, has raised a couple of million dollars to print what it calls see-through “pods” or “micro-cradles.” The idea is that once an egg is plopped into one, it can be handled more easily and connected to other devices, such as pumps to add solutions in minute quantities.

Inside one of Fertilis’s pods, an egg sits in a chamber no larger than a bead of mist, but the container itself is large enough to pick up with small tongs. Fertilis has published papers showing it can flash-freeze eggs inside the cradles and fertilize them there, too, by pushing in a sperm with a needle.

A human egg is about 0.1 millimeters across, at the limit of what a human eye can see unaided. Right now, to move one, an embryologist will slurp it up into a hollow needle and squirt it out again. But Thompson says that once inside the company’s cradles, eggs can be fertilized and grow into embryos, moving through the stations of a robotic lab as if on a conveyor belt. “Our whole story is minimizing stress to embryos and eggs,” he says.

Thompson hopes someday, when doctors collect eggs from a woman’s ovaries, they’ll be deposited directly into a micro-cradle and, from there, be nannied by robots until they’re healthy embryos. “That’s my vision,” he says.

FERTILIS

MIT Technology Review found one company, AutoIVF, a spinout from a Massachusetts General Hospital–Harvard University microfluidics lab, that has won more than $4 million in federal grants to develop such an egg-collecting system. It calls the technology “OvaReady.”

Egg collection happens after a patient is treated with fertility hormones. Then a doctor uses a vacuum-powered probe to hoover up eggs that have ripened in the ovaries. Since they’re floating in liquid debris and encased in protective tissue, an embryologist needs to manually find each one and “denude” it by gently cleaning it with a glass straw.