The new changes affect Provisions on the Management of Internet Post Comments Services, a regulation that first came into effect in 2017. Five years later, the Cyberspace Administration wants to bring it up to date.

“The proposed revisions primarily update the current version of the comment rules to bring them into line with the language and policies of more recent authority, such as new laws on the protection of personal information, data security, and general content regulations,” says Jeremy Daum, a senior fellow at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center.

The provisions cover many types of comments, including anything from forum posts, replies, messages left on public message boards, and “bullet chats” (an innovative way that video platforms in China use to display real-time comments on top of a video). All formats, including texts, symbols, GIFs, pictures, audio, and videos, fall under this regulation.

There’s a need for a stand-alone regulation on comments because the vast number makes them difficult to censor as rigorously as other content, like articles or videos, says Eric Liu, a former censor for Weibo who’s now researching Chinese censorship at China Digital Times.

“One thing everyone in the censorship industry knows is that nobody pays attention to the replies and bullet chats. They are moderated carelessly, with minimum effort,” Liu says.

But recently, there have been several awkward cases where comments under government Weibo accounts went rogue, pointing out government lies or rejecting the official narrative. That could be what has prompted the regulator’s proposed update.

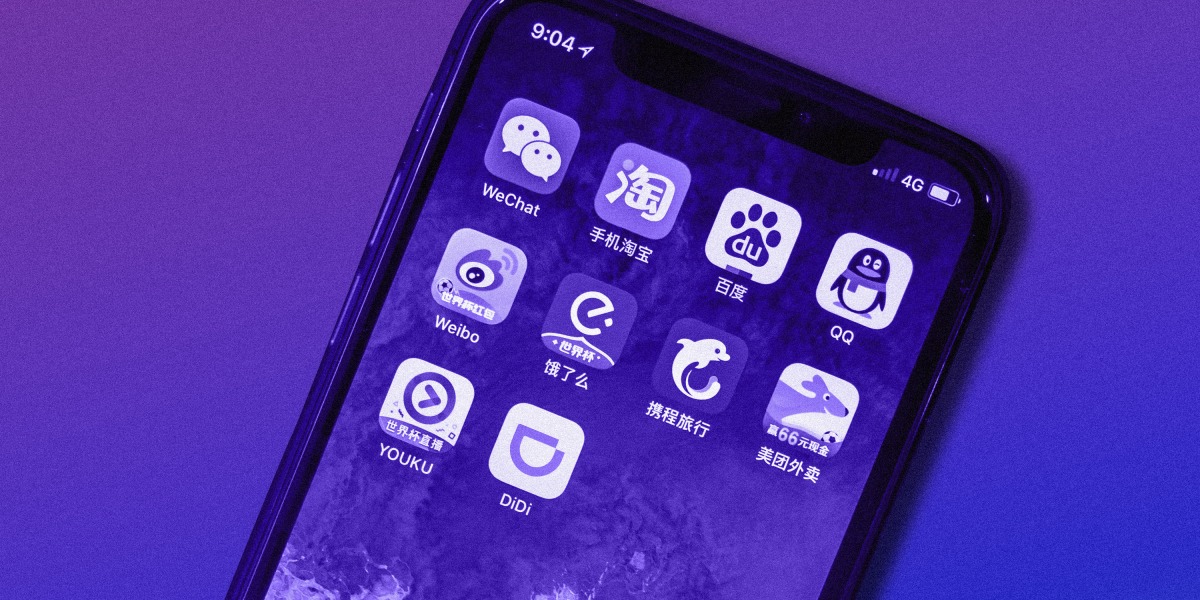

Chinese social platforms are currently on the front lines of censorship work, often actively removing posts before the government and other users can even see them. ByteDance famously employs thousands of content reviewers, who make up the largest number of employees at the company. Other companies outsource the task to “censorship-for-hire” firms, including one owned by China’s party mouthpiece People’s Daily. The platforms are frequently punished for letting things slip.

Beijing is constantly refining its social media control, mending loopholes and introducing new restrictions. But the vagueness of the latest revisions makes people worry that the government may ignore practical challenges. For example, if the new rule about mandating pre-publish reviews is to be strictly enforced—which would require reading billions of public messages posted by Chinese users every day—it will force the platforms to dramatically increase the number of people they employ to carry out censorship. The tricky question is, no one knows if the government intends to enforce this immediately.