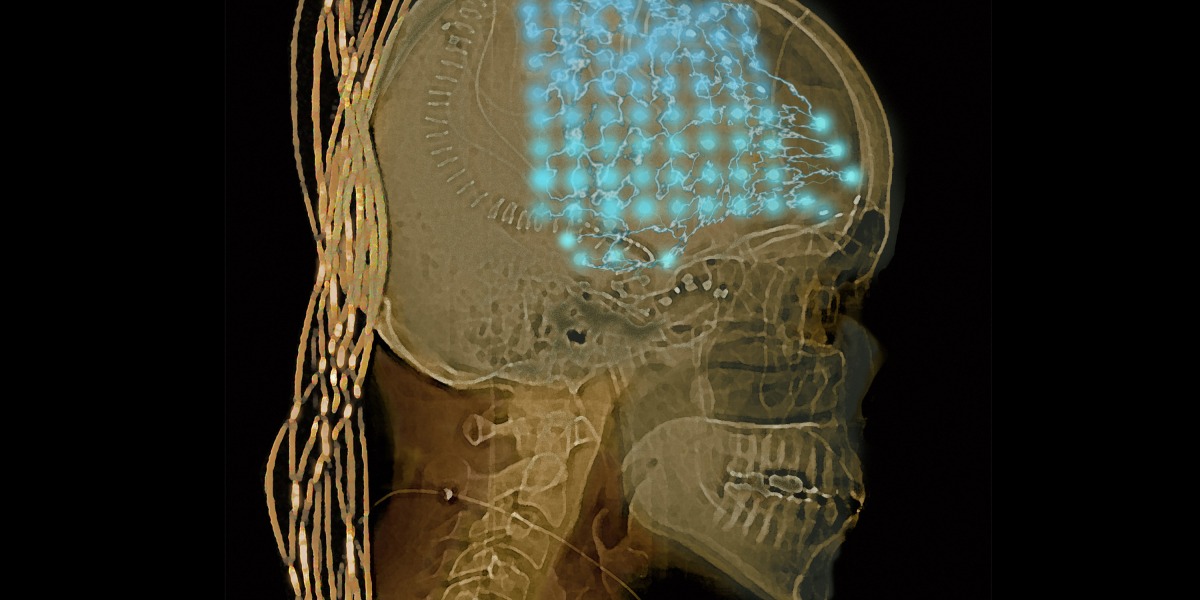

Ghuman, Wang, and their colleagues turned to people who were undergoing brain surgery for epilepsy. Some people with severe or otherwise untreatable epilepsy opt to have the small parts of their brain that trigger their seizures surgically removed. Before any operation, they may have electrodes implanted in their brains for a week or so. During that time, these electrodes monitor brain activity to help surgeons pinpoint where their seizures start and identify exactly which bit of brain should be removed.

The researchers recruited 20 such individuals to volunteer in their study. Each person had 10 to 15 electrodes implanted for somewhere between three and 12 days.

The pair collected recordings from the electrodes over the entire period. The volunteers were all in hospital while they were monitored, but they still did everyday things like eating meals, talking to friends, watching TV, or reading books. “We know so little about what the brain does during these real, natural behaviors in a real-world setting,” says Ghuman.

The edge of chaos

The team found some surprising patterns in brain activity over the course of the week. Specific brain networks seemed to communicate with each other in what looked like a “dance,” with one region appearing to “listen” while the other “spoke,” say the researchers, who presented their findings at the Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego last year.

And while the volunteers’ brains seemed to pass between different states over time, they did so in a curious way. Rather than simply moving from one pattern of activity to another, their brains appeared to zip between several other states in between, apparently at random. As the brain shifts from one semi-stable state to another, it seems to embrace chaos.