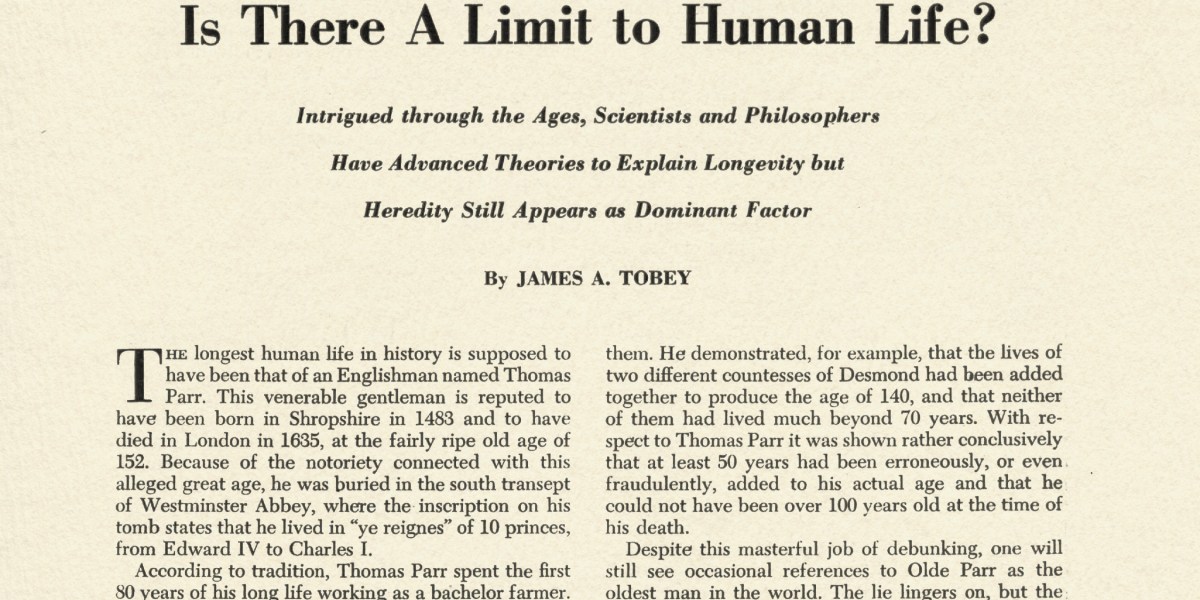

People have always been fascinated with the question of human longevity. In this 1954 piece for Technology Review, James A. Tobey, author of more than a dozen books on public health, including Your Diet for Longer Life (1948), noted that despite a few frauds claiming to be older than 150, “the consensus of scientific opinion is that there is a definite limit to human life, a limit now and perhaps forever in the vicinity of 100 years.”

In 1954, the average life expectancy of an American at birth had risen to 68 years from 47 in 1900. But most of the advances came not from old people living longer but from infants avoiding death before their first birthday. The average person’s chances of living to 100 in mid-20th-century America, Tobey observed, were “no better than they were in the days of the Roman Empire.”

We have done better since then: average life expectancy reached nearly 79 years in the US before declining in recent years, largely as a result of the covid-19 pandemic. But as this issue of TR reveals, the quest to keep extending the upper limit on our years lives on.