Drawing from DARPA’s blueprint, ARPA-E was created as part of the Department of Energy in 2007 to drive similar innovations in energy. Since then, it’s awarded over $3 billion in funding to over 1,400 projects in advanced energy research, and it’s helped bring innovative technologies to market. US Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm has called it the government’s energy “moonshot factory.”

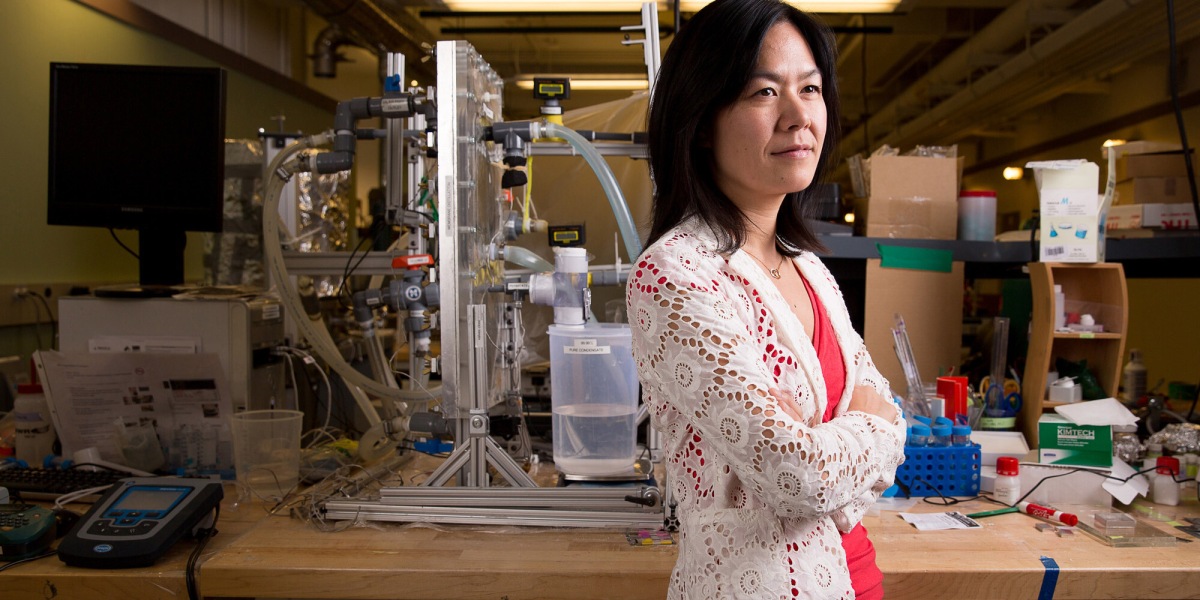

ARPA-E swore in its new director, Evelyn Wang, in January. Wang is taking leave from her position as head of the Department of Mechanical Engineering at MIT to steer the agency. We sat down to talk about what’s coming next for energy technology, what challenges lie ahead, and how to measure progress in early-stage research. Here are a few excerpts from our conversation, edited for clarity and length.

What do you see as ARPA-E’s role in advancing energy technology today, and how does it relate to the broader Department of Energy?

Energy technologies take sometimes a decade or so to be really deployed in a meaningful and impactful way. I think a lot of the work that the rest of the Department of Energy often focuses on has a road map, and they focus on the near-term wins.

We’re really focused on the high-risk, high-reward, potentially transformative energy technologies, and I think we span a pretty large space in terms of taking something from the fundamental aspects to the practical realization of a prototype that can be potentially commercialized in the future.

And so I think there are complementary aspects, but often we diverge because of the fact that we’re working on these really risky, longer-term technological innovations. That’s where ARPA-E is a huge force, because of the fact that we really take things that we don’t know if it’s going to work or not, but it potentially could transform the energy landscape. And that’s something I think that many other agencies don’t traverse.

What are some potential areas that are ripe for innovation in energy?

In the near term, we are thinking a lot about how we improve semiconductor materials, for example, to create a more capable grid. And we want to think about how we underground our grid—taking cables underground is really important in a lot of our recent efforts.