These immune-dampening shots could lead to a whole host of therapies to treat autoimmune diseases. In fact, Anokion, a company Hubbell cofounded, has already launched clinical trials to test whether this type of inverse vaccine might help people with multiple sclerosis and celiac disease. It’s an exciting prospect, so for The Checkup this week, let’s take a look at inverse vaccines.

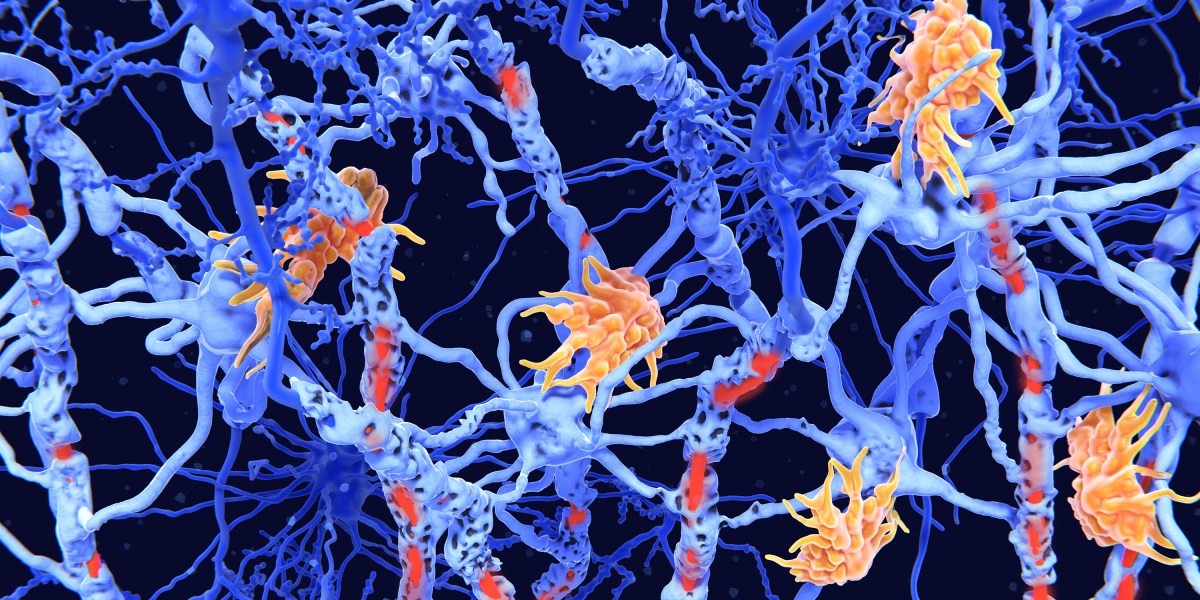

How do these vaccines work? Let’s start with a little immunology 101. We tend to think of our immune system as a beefy bodyguard, fighting off pathogens that seek to harm us. But it has another, equally important job. “Mostly our immune system ignores stuff that it’s being exposed to all the time,” says Megan Levings at the BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute in Vancouver (and a member of Anokion’s scientific advisory board). That includes “all the food we eat, all the bacteria that live on our bodies, all the funguses and mold in the environment.” The capacity to ignore—known as immune tolerance—isn’t passive. The immune system learns which things are dangerous and which are not, and stores that memory in specialized cells. When the system makes a mistake and flags a harmless protein as dangerous, the mixup can cause serious problems—allergies, autoimmune diseases, and other types of immune disorders.

With traditional vaccines, the goal is to deliver a foreign substance in a way that raises alarms. That’s why vaccines are often combined with ingredients called adjuvants, which provoke a stronger immune response. (mRNA vaccines don’t need adjuvants because the immune system already sees genetic material as a threat.) With inverse vaccines, also called tolerogenic vaccines because they provoke tolerance, the goal is to train the immune system to recognize that a particular target is harmless.

I should point out that the idea of tolerogenic vaccines is not new. Researchers have been working on them for decades, trying different methods for delivering the desired vaccine targets—called antigens—without provoking an immune response. But until now they’ve had little success.

Hubbell’s group has developed a technique that involves adding a sugar to the antigen, which ensures that it travels to the liver. Why the liver? The organ has the ability to tag molecules with “harmless” labels. “It’s actually harnessing normal biology,” Levings says. (For a deeper dive into the paper, read Eric Topol’s newsletter, Ground Truths. That’s where I learned about the concept of inverse vaccines.)

But adding a sugar isn’t the only way to develop an inverse vaccine. In 2021, a team from BioNTech and the Johannes Gutenberg University reported that they had developed a tolerogenic mRNA vaccine able to curb symptoms in several mouse models of multiple sclerosis. That’s especially impressive given that mRNA tends to be so very good at prompting an immune response. The researchers achieved this by altering the fatty nanoparticle that carries the mRNA, but the exact mechanism wasn’t totally clear even to Levings, who wrote a commentary on the paper.

Taking these therapies from bench to bedside won’t be easy. It’s tricky for a few different reasons, says Lawrence Steinman, a neuroimmunologist at Stanford University. First, with a complex disease such as multiple sclerosis, no single antigen is wholly responsible. So do you pick one, or “do you want to make a complex mixture of many of those antigens?” Steinman asks.

There’s also the challenge of proving that the vaccine works. The treatments for many autoimmune diseases have gotten much better over the years. About 15 years ago, Steinman led a clinical trial to test a tolerogenic DNA vaccine in patients with multiple sclerosis. The vaccine worked, but not better than cutting-edge therapies. “We had a modest beneficial effect in reducing inflammation in the brain. But it could not compete with some of the drugs that were just coming on the market,” he says. Now Steinman serves as chairman for a company called Pasithea Therapeutics, and he’s working on a new inverse DNA vaccine for multiple sclerosis. This one will target a protein in the brain that mimics a portion of the Epstein-Barr virus, which may be a trigger for MS.