The record-breaking heat wave in China, which started back in June, has evaporated over half the hydroelectricity generation capacity in Sichuan, a southwestern province that usually gets 81% of its electricity from hydropower plants. That decreased energy supply, at a time when the need for cooling has increased demand, is putting industrial production and everyday life in the region on pause.

And as the power supply has become unreliable, the government has instituted EV charging restrictions in order to prioritize more critical daily electricity needs.

As Chinese publications have reported, finding a working charging station in Sichuan and the neighboring region Chongqing—a task that took a few minutes before the heat wave—took as long as two hours this week. The majority of public charging stations, including those operated by leading EV brands like Tesla and China’s NIO and XPeng, are closed in the region because of government restrictions on commercial electricity usage.

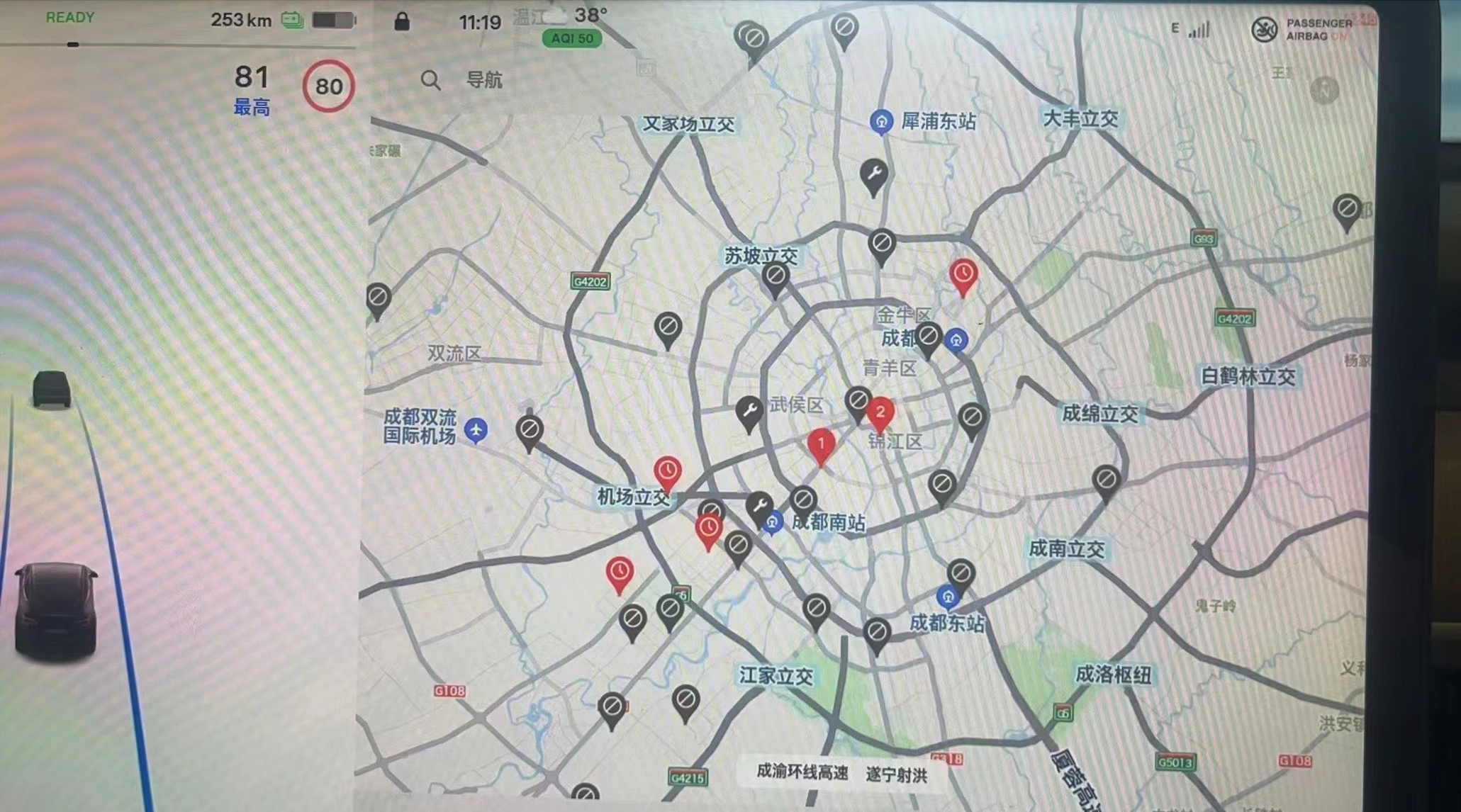

A screenshot sent to MIT Technology Review by a Chinese Tesla owner in Sichuan, who asked not to be named for privacy reasons, shows that on August 24, only two of the 31 Tesla Supercharger Stations in or near the province’s capital city of Chengdu were working as normal.

In addition to facing mandatory service suspensions, EV owners are also being encouraged or forced to charge only during off-peak hours. In fact, the leading domestic operator, TELD, has closed over 120 charging stations in the region from 8 a.m. to midnight, the peak hours for electricity usage. State Grid, China’s largest state-owned electric utility company, also builds and operates EV charging stations; it announced on August 19 that in three provinces that have over 140 million residents and 800,000 electric vehicles in total, the company will offer 50% off coupons if drivers charge at night. State Grid is also reducing the efficiency of 350,000 charging posts during the day, so the individual charging time for vehicles would be five to six minutes longer but the total power consumed during peak hours would go down.

The impact is evident in videos shared on Chinese social media, which show long lines of EVs waiting outside the few working charging stations, even after midnight. Electric taxi drivers have been hit especially hard, as their livelihoods depend on their vehicles. “I started waiting in the line at 8:30 p.m. yesterday and I only started charging at around 5 a.m.,” a Chengdu taxi driver told an EV influencer. “You are basically always waiting in lines. Like today, I didn’t even get much business, but I’m in the line again now. And the battery is going down quickly.”

The charging challenges are also pushing some people back into using fossil fuel. The Tesla owner in Sichuan is planning to visit Chengdu for work this week but decided to drive his other car, a gas-powered one, for fear that he wouldn’t find a place to recharge before returning home. Another driver from Chengdu, who owns a plug-in hybrid, told MIT Technology Review that she switched to gas this week even though she usually sticks to electricity because it’s slightly cheaper.

The sudden difficulty of charging in Sichuan and neighboring provinces has caught the EV industry by surprise. “A large-scale power shortage like this is still something we’ve never seen [in China],” says Lei Xing, an auto industry analyst and the former chief editor at China Auto Review. He says the climate disaster is reminding the industry that while China leads the world on many EV adoption metrics, there are still infrastructure weaknesses that need to be addressed. “It feels like China already has a good charging infrastructure … but once something like these power restrictions happens, the problems are exposed. All EV owners who rely on public charging posts are having troubles now,” Xing says.