Most research into the microbiome has focused on the trillions of bugs that live in our guts. But our skin is also home to multiple microbial ecosystems. The community that lives in your armpit could look quite different from the community that lives on your eyelids. We are still figuring out exactly what these microbes are doing, but they seem to feed on our secretions, possibly produce some beneficial secretions of their own, and protect us from infections.

They also appear to influence the way our immune systems work. A growing body of research suggests that microbes living in and on our bodies can amplify or turn down the immune response to something that might potentially cause us harm—whether it’s an infection, a tumor, or something more benign.

Simply introducing a microbe to the skin of an animal can also trigger an immune response—albeit one that doesn’t cause all the usual signs of an infection, like pain, fever, or sickness. This is somewhat surprising, says Michael Fischbach at Stanford University, because these microbes don’t tend to be harmful: “They’re our friends.” Adding a microbe to the skin of a mouse, for example, can have an effect similar to giving the same mouse a vaccination, he says.

Modified microbes

Fischbach and his colleagues wondered if they might be able to hijack this effect to tweak the immune response.

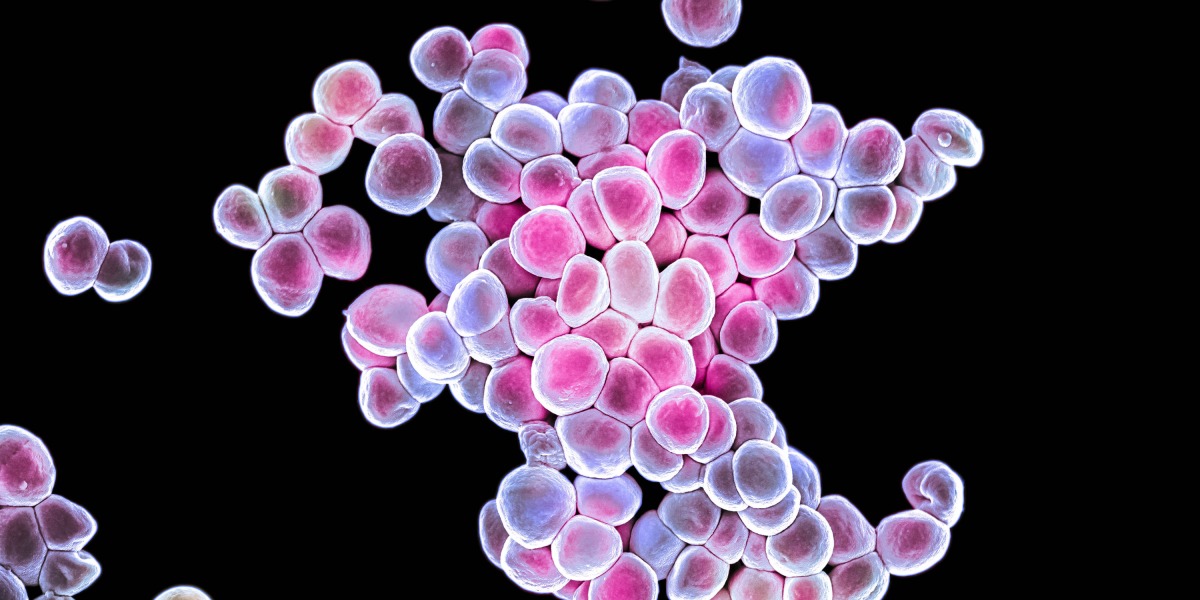

The team started the investigation by choosing a microbe that is commonly found on human skin. S. epidermidis is thought to be a member of the human microbiome, and it doesn’t typically cause disease. The microbes the researchers used were originally collected from behind the ear of a human volunteer, says Fischbach.

The researchers modified these microbes by inserting a new gene into them. The gene codes for a protein that sits on the surface of some cancer cells. The idea is that if the immune system generates cells that recognize the microbe, these cells will also recognize tumors.

The team then applied these “designer bugs” to mice by wiping them over the heads of the animals with a cotton bud. Another group of mice had regular, unmodified samples of the bacteria smeared onto them. In both cases, the microbes quickly made a home for themselves on the mice’s skin, says Fischbach.

At the same time, the mice were injected with skin cancer cells. These cells were taken from other mice that had cancer, so they had the target protein on their surface.