That could be avoided if, instead of using hormones to stimulate the person’s ovaries to release mature eggs, doctors could remove pieces of the ovaries themselves, and somehow obtain mature eggs in the lab. This would involve taking immature eggs and coaxing them along in their development, to the stage at which they can be fertilized by sperm.

This has already been achieved in some people who have survived cancer. Some cancer treatments are toxic, especially to eggs and sperm. Adults are often advised to store healthy eggs or sperm before they begin these treatments. But that’s not an option for children who haven’t yet been through puberty.

If children have parts of their ovaries removed, however, some clinics have been able to use this tissue to later generate mature eggs and fertilize them with sperm, implanting the resulting embryo back into those same people when they are adults. The technique appears to work, and healthy babies have been born. Last year, three US-based reproductive medicine societies issued a statement concluding that the technique should no longer be considered experimental.

The technique has not yet been used to help transgender people have babies, but Christodoulaki and her colleagues believe it might. To find out, they tried the approach in ovaries donated by trans men.

The team started with ovaries donated by 14 transgender men aged between 18 and 24, who had had the organs removed as part of their gender-affirming treatment. All the participants had been undergoing testosterone therapy for an average of 26 months, and some were also taking a drug to stop them from menstruating.

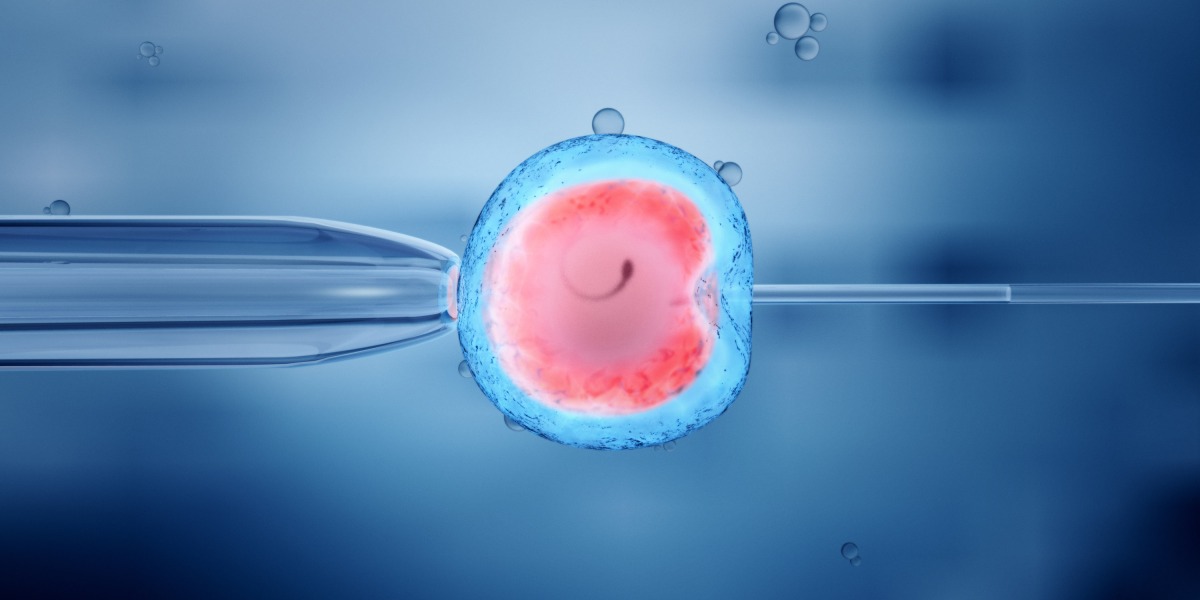

First, the team removed eggs that were days away from being released by the ovary. The team repeated the process with similarly immature eggs donated by cisgender women. After 48 hours in a lab dish, the eggs appeared to be ready to be fertilized with sperm.

In both cases, around half the immature eggs were successfully matured in the lab. But something appeared to go wrong when the team tried to fertilize the eggs with sperm. While 84% of the eggs from cisgender women could be fertilized, the figure was only around 45% for trans men.

By the time the embryos were five days old—the point at which they would normally be transferred into a person’s uterus—only 2% of those generated from trans men’s eggs were still alive, compared with 25% of the embryos from cis women’s eggs.