So far, B cells haven’t gotten the same attention—indeed, genetically engineered versions have never been tested in a human. That’s partly because “engineering B cells is not that easy,” says Xin Luo, a professor at Virginia Tech who in 2009 demonstrated how to generate B cells that have an added gene.

That early work, carried out at Caltech, explored whether the cells could be directed to make antibodies against HIV, perhaps becoming a new form of vaccination.

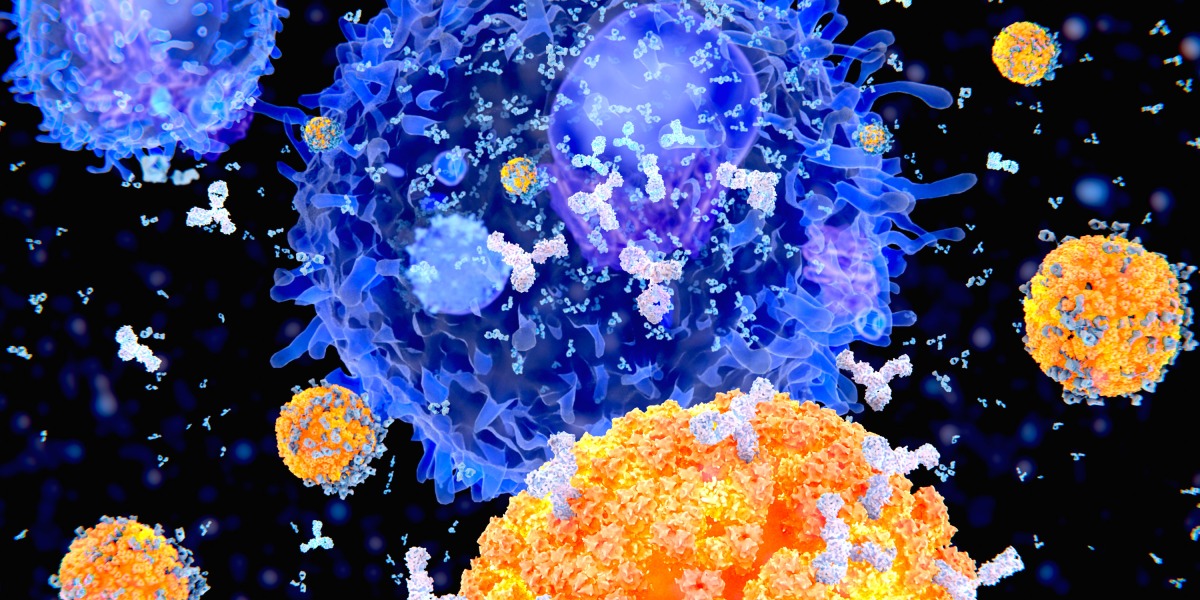

While that idea didn’t pan out, now biotech companies like Immusoft, Be Biopharma, and Walking Fish Therapeutics want to harness the cells as molecular factories to treat serious rare diseases. “These cells are powerhouses for secreting protein, so that’s something they want to take advantage of,” says Luo.

Immusoft licensed the Caltech technology and got an early investment from Peter Thiel’s biotech fund, Breakout Labs. Company founder Matthew Scholz, a software developer, boldly predicted in 2015 that a trial could start immediately. However, the technology the company terms “immune-system programming” didn’t turn out to be as straightforward as coding a computer.

Ainsworth says Immusoft had to first spend several years working out reliable ways to add genes to B cells. Instead of using viruses or gene editing to make genetic changes, the company now employs a transposon—a molecule that likes to cut and paste DNA segments.

It also took time to convince the FDA to allow the trial. That’s because it’s known that if added DNA ends up near cancer-promoting genes, it can sometimes turn them on.

“The FDA is concerned if you are doing this in a B cell, could you develop a leukemia situation? That is something that they are going to watch pretty closely,” says Paul Orchard, the doctor at the University of Minnesota who will be recruiting patients and carrying out the study.

B-cell factories

The first human test could resolve some open questions about the technology. One is whether the enhanced cells will take up long-term residence inside people’s bone marrow, where B cells typically live. In theory, the cells could survive decades—even the entire life of the patient. Another question is whether they’ll make enough of the missing enzyme to help stall MPS, which is a progressive disease.