A team of researchers led by Pratyusha Sharma at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab (CSAIL) working with Project CETI, a nonprofit focused on using AI to understand whales, used statistical models to analyze whale codas and managed to identify a structure to their language that’s similar to features of the complex vocalizations humans use. Their findings represent a tool future research could use to decipher not just the structure but the actual meaning of whale sounds.

The team analyzed recordings of 8,719 codas from around 60 whales collected by the Dominica Sperm Whale Project between 2005 and 2018, using a mix of algorithms for pattern recognition and classification. They found that the way the whales communicate was not random or simplistic, but structured depending on the context of their conversations. This allowed them to identify distinct vocalizations that hadn’t been previously picked up on.

Instead of relying on more complicated machine-learning techniques, the researchers chose to use classical analysis to approach an existing database with fresh eyes.

“We wanted to go with a simpler model that would already give us a basis for our hypothesis,” says Sharma.

“The nice thing about a statistics approach is that you do not have to train a model and it’s not a black box, and [the analyses are] easier to perform,” says Felix Effenberger, a senior AI research advisor to the Earth Species Project, a nonprofit that’s researching how to decode non-human communication using AI. But he points out that machine learning is a great way to speed up the process of discovering patterns in a data set, so adopting such a method could be useful in the future.

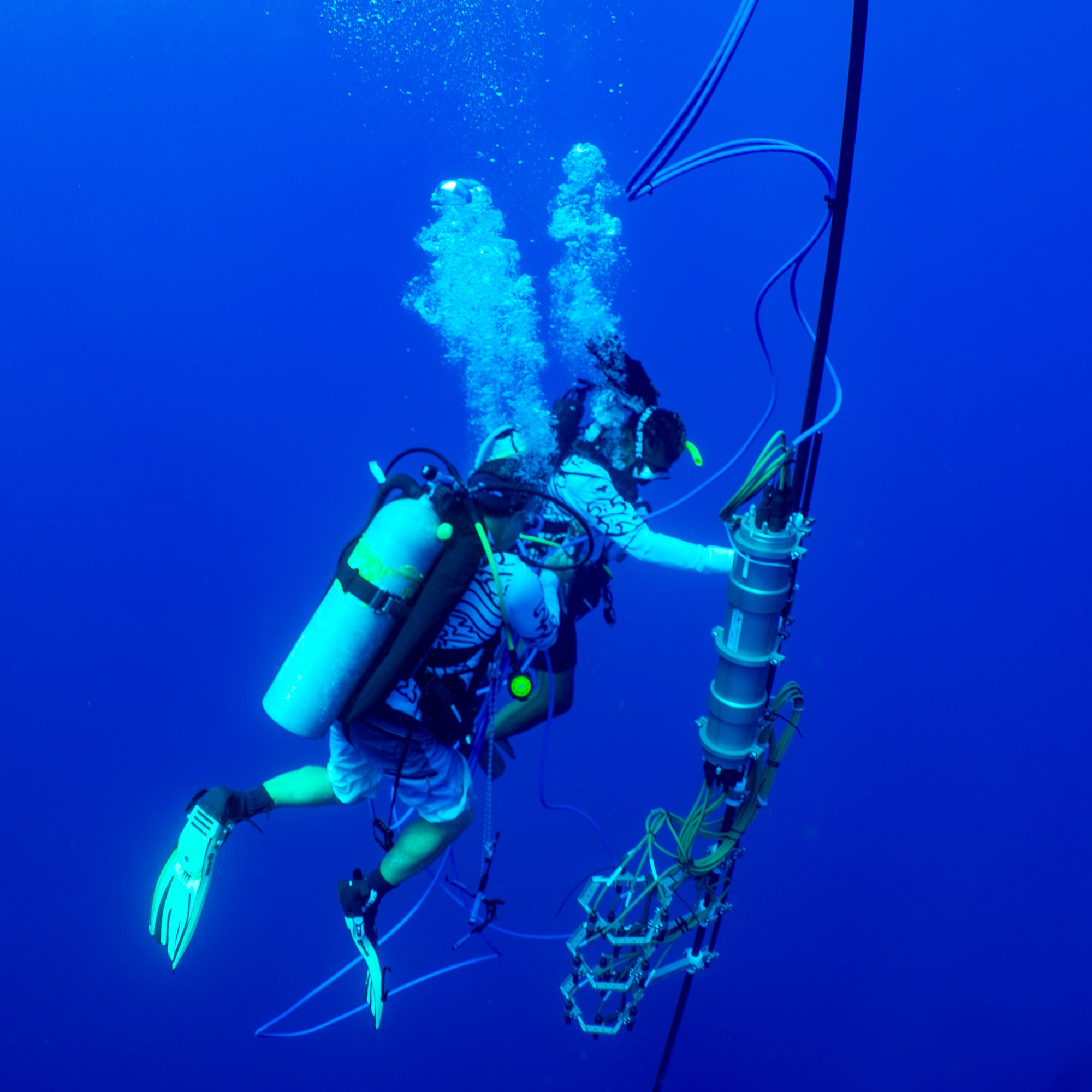

DAN TCHERNOV/PROJECT CETI

The algorithms turned the clicks within the coda data into a new kind of data visualization the researchers call an exchange plot, revealing that some codas featured extra clicks. These extra clicks, combined with variations in the duration of their calls, appeared in interactions between multiple whales, which the researchers say suggests that codas can carry more information and possess a more complicated internal structure than we’d previously believed.

“One way to think about what we found is that people have previously been analyzing the sperm whale communication system as being like Egyptian hieroglyphics, but it’s actually like letters,” says Jacob Andreas, an associate professor at CSAIL who was involved with the project.

Although the team isn’t sure whether what it uncovered can be interpreted as the equivalent of the letters, tongue position, or sentences that go into human language, they are confident that there was a lot of internal similarity between the codas they analyzed, he says.

“This in turn allowed us to recognize that there were more kinds of codas, or more kinds of distinctions between codas, that whales are clearly capable of perceiving—[and] that people just hadn’t picked up on at all in this data.”

The team’s next step is to build language models of whale calls and to examine how those calls relate to different behaviors. They also plan to work on a more general system that could be used across species, says Sharma. Taking a communication system we know nothing about, working out how it encodes and transmits information, and slowly beginning to understand what’s being communicated could have many purposes beyond whales. “I think we’re just starting to understand some of these things,” she says. “We’re very much at the beginning, but we are slowly making our way through.”

Gaining an understanding of what animals are saying to each other is the primary motivation behind projects such as these. But if we ever hope to understand what whales are communicating, there’s a large obstacle in the way: the need for experiments to prove that such an attempt can actually work, says Caroline Casey, a researcher at UC Santa Cruz who has been studying elephant seals’ vocal communication for over a decade.

“There’s been a renewed interest since the advent of AI in decoding animal signals,” Casey says. “It’s very hard to demonstrate that a signal actually means to animals what humans think it means. This paper has described the subtle nuances of their acoustic structure very well, but taking that extra step to get to the meaning of a signal is very difficult to do.”