The EU is currently negotiating a new law called the AI Act, which will ban member states, and maybe even private companies, from implementing such a system.

The trouble is, it’s “essentially banning thin air,” says Vincent Brussee, an analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies, a German think tank.

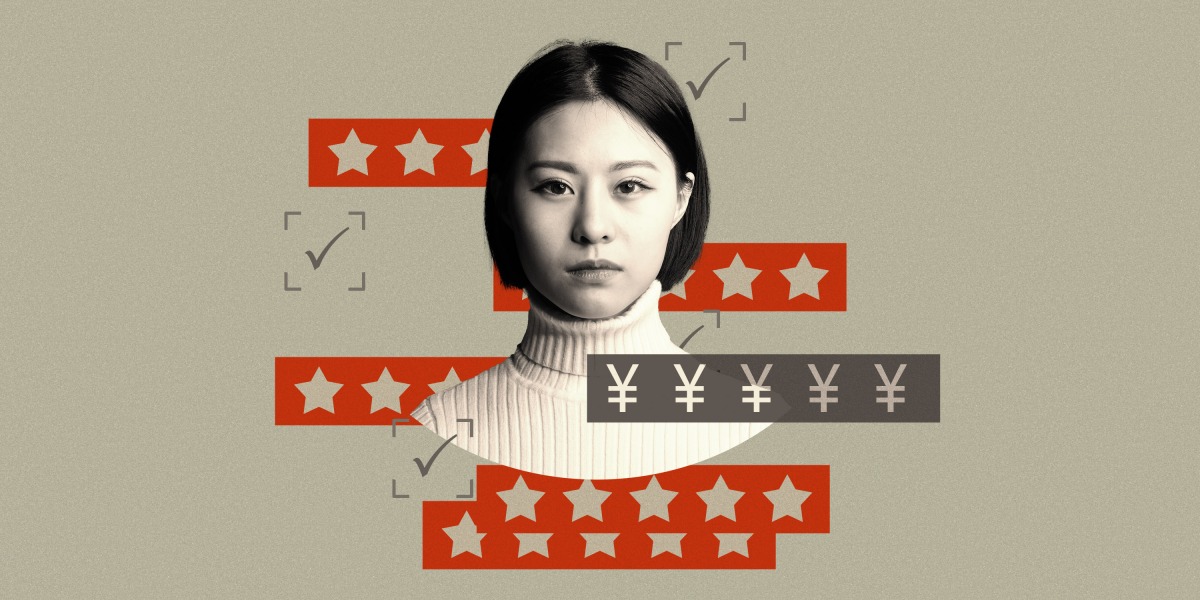

Back in 2014, China announced a six-year plan to build a system rewarding actions that build trust in society and penalizing the opposite. Eight years on, it’s only just released a draft law that tries to codify past social credit pilots and guide future implementation.

There have been some contentious local experiments, such as one in the small city of Rongcheng in 2013, which gave every resident a starting personal credit score of 1,000 that can be increased or decreased by how their actions are judged. People are now able to opt out, and the local government has removed some controversial criteria.

But these have not gained wider traction elsewhere and do not apply to the entire Chinese population. There is no countrywide, all-seeing social credit system with algorithms that rank people.

As my colleague Zeyi Yang explains, “the reality is, that terrifying system doesn’t exist, and the central government doesn’t seem to have much appetite to build it, either.”

What has been implemented is mostly pretty low-tech. It’s a “mix of attempts to regulate the financial credit industry, enable government agencies to share data with each other, and promote state-sanctioned moral values,” Zeyi writes.

Kendra Schaefer, a partner at Trivium China, a Beijing-based research consultancy, who compiled a report on the subject for the US government, couldn’t find a single case in which data collection in China led to automated sanctions without human intervention. The South China Morning Post found that in Rongcheng, human “information gatherers” would walk around town and write down people’s misbehavior using a pen and paper.